Texas: Supporting the Right to Present a Defense Through Defense Investigations

Preliminary Report & Recommendations to the Texas Indigent Defense Commission

This report examines the use of defense investigators in court-appointed cases across the state of Texas. One of the initial steps in the process was for us to survey Texas investigators to understand their perspectives on how they were being utilized and what barriers, if any, existed in serving as defense investigators in court-appointed cases. Additional information, such as years of experience, level of education, and prior training in law enforcement, were also collected in the survey. The investigator survey was followed by a similar survey for defense attorneys.

In completing the survey, both defenders and investigators were asked to identify the primary jurisdiction in which they worked and up to six secondary jurisdictions. Regarding the geographic representation of the survey respondents, the investigators reported working in 133 of the 254 counties, while attorneys reported working in 205 counties. Forty one counties had no responses from either an attorney or an investigator, although some respondents in both surveys indicated that they provided statewide coverage. Additionally, we conducted qualitative interviews of judges, investigators, and public defense lawyers from selected jurisdictions. The analysis of those surveys and interviews, along with the associated legal, ethical, and empirical research, formed the basis for this report and recommendations.

Reports indicate the courts in some jurisdictions may be a critical barrier to the use of investigators in court-appointed cases. For example, a 2019 Tarrant County monitoring report indicated the total amount of funds for investigative services in misdemeanor cases for the fiscal year was less than one-half of 1% of the overall court-appointed expenditures. Felony expenditures did not fare much better, with the total defense investigator expenditures for the county representing just over 3% of the total felony expenses. When asked what might explain the low expenditures, some attorneys indicated that judges discouraged use of defense investigators by frequently refusing to approve funds and cutting vouchers for work that was completed.

During our interviews with judges in counties with zero investigator expenditures, only one judge mentioned reducing investigator invoices, explaining that they only reduce invoices when the investigator double-charges, such as charging for both mileage and travel time to interview a witness. In court-appointed cases, judges make decisions to authorize funds to hire an investigator, the amount of funding, and the amount ultimately to be paid to the investigator after the work has been completed.

In one county with zero reported expenditures, two judges reported that they receive and approve requests for investigators daily. Both judges stated that they routinely approve these requests if they are submitted with the correct information (e.g., name of investigator or firm, type of case, and what the investigator will perform for the amount requested). In another county with zero expenditures, a judge reported via email,

The only thing I do is approve their requests when made. Which in my experience has been very seldom. I can only really remember one time in the past 5 years that I’ve gotten a request for an investigator from them….

When asked about the costs of investigators, one judge described that a judge’s role is to “balance the need to be a good steward of the county’s funds with the need to provide a robust defense.” A second judge stated that judges must be mindful of taxpayer funds, and not to waste those funds:

I just don’t hand out court-appointed lawyers, nor do I appoint investigators or expert witnesses like a bag of lollipops because once again, I’m conscious of who has to pay for these. But if the need is there, absolutely. And certainly an indigent person is entitled to representation, and we don’t quibble about that. But I do look hard at appointing investigators. I just don’t want a lawyer to say, ‘Well, I’m just going to sit in my office, and I’m going to have the taxpayers pay for an investigator to go out and talk to witnesses', when it’s their damn job to do so. That aggravates me.

Investigator Findings

This report also explores the availability and interests of investigators to better understand the relationship between defense attorneys and defense investigators in Texas. According to the Department of Public Safety, there are 33,734 persons with active private investigator licenses in Texas. These individuals work for one or more of the 2,436 licensed investigator agencies (of which 2,280 have a physical address in Texas). One-third of these agencies have physical addresses in one of five major cities: Austin (103), Dallas (159), Fort Worth (80), Houston (301), and San Antonio (128).

Our investigator survey repondents reported working in Dallas (16), Harris (14), and El Paso (7) counties, with

60% providing services in more than 1 county. Roughly half of all (51%) responding investigators had previous law enforcement experience.

About 2% of investigators responded that they had federal agency experience or worked as a parole officer. Of the respondents with former law enforcement experience, roughly 70% worked in Texas in the area in which they continue to work. In terms of years of experience, 38% responded that they had served as a defense investigator for less than 5 years, 26% served as a defense investigator for 6 to 10 years, 15% served as a defense investigator for 11 to 15 years, and 22% served as a defense investigator for 16 or more years.

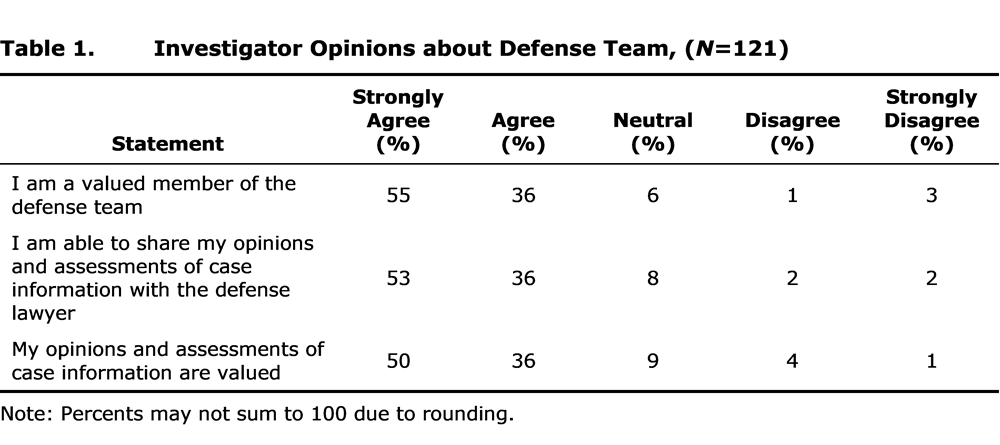

In terms of working with defense attorneys, 55% strongly agreed and 36% agreed that they felt like a valued member of the defense team (Table 1). About 4% of investigators disagreed or strongly disagreed with that statement. Furthermore, 53% of investigators strongly agreed that they were able to share opinions about the case with the defense team, and 50% strongly agreed that the defense team valued their assessments of the cases.

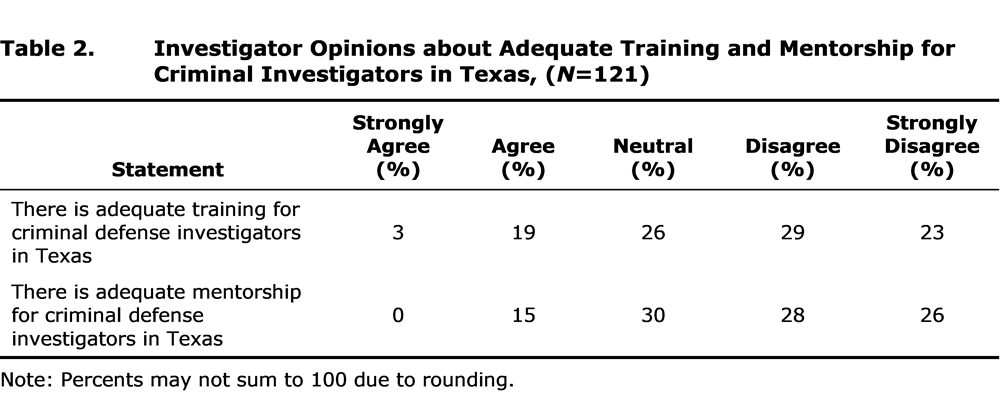

Investigators were asked whether they agreed that there is adequate training and adequate mentorship for criminal investigators in Texas. Table 2 summarizes their responses. Overall, more than half of all investigators disagreed or strongly disagreed that there is adequate training for defense investigators (52%) or adequate mentoring for defense investigators (54%) in Texas.

Investigators were given a list of tasks and asked to identify up to 3 tasks that they felt they had the most skill or expertise in completing. 90% of investigators responded that locating and interviewing witnesses was their best skill, followed by 63% building relationships with clients and their loved ones, and 45% examining and assessing evidence collected by police.

Defense Attorney Findings

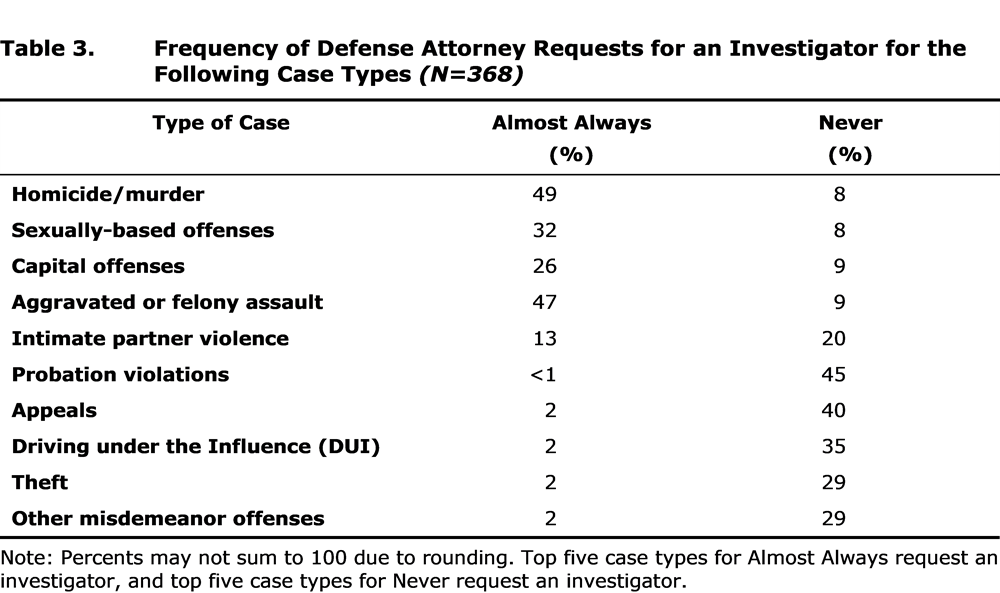

While the survey of defense attorneys did not ask about the time spent on investigations, the survey did ask how frequently defenders requested investigators by different case types. Table 3 shows the frequency of responses for case types in which an investigator is “Almost Always” requested an investigator compared to case when an investigator is “Never” to better understand the culture of using investigators. As expected, defense attorneys most frequently request investigators for more serious charges. Surprisingly, almost 10% of defense attorneys never request the services of investigators for homicides, sexually-based offenses, capital offenses or aggravated assault, and 20% of defenders reported never requesting investigators for intimate partner violence cases.

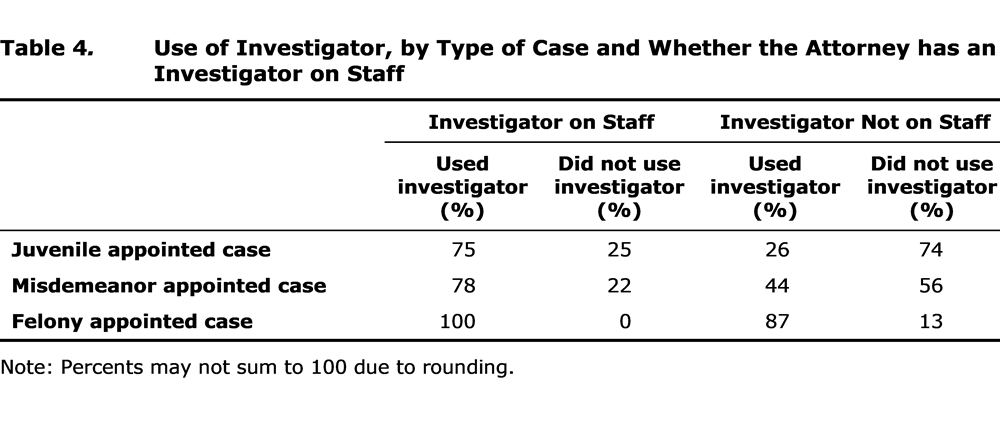

Consistent with the findings of the TIDC Caseload Study, most defense attorneys strongly agreed (35%) or agreed (29%) that criminal defense attorneys should use the services of investigators more frequently. When asked why they may not request the services of an investigator, 44% of defense attorneys Strongly Agreed or Agreed that they typically do their own investigations. Notably, very few attorneys (roughly 12%) identified fear of reprisal from the court as a reason to not request investigators. Of attorneys surveyed, 58% strongly agreed with the statement that investigators are a valued member of the defense team, and 53% strongly agreed that they value investigator opinions and assessments. Furthermore, the use of investigators varied by whether defense attorneys had investigators on staff; 21% of defenders (n=76) reported they have an investigator on staff. Table 4 shows the type of case and reported use of investigator, by whether there is an investigator on staff.

Defense attorneys who reported having an investigator on staff also reported increased frequency of using investigators for a wider range of case types. For example, only 26% of juvenile appointed cases involved the use of an investigator, while 75% of defense attorneys with investigators on staff reporting using investigators in juvenile appointed cases.

Relatedly, investigator interviews revealed that in many jurisdictions, when a defense lawyer makes a motion for funds for an expert, they are expected to identify a specific investigator by name that they plan to use for their case. These investigators revealed they frequently work with the same cadre of attorneys and when they connect with a new lawyer, it is typically through a referral from a lawyer the investigator frequently works with. This can make it difficult for newer attorneys or those who do not typically use investigators, to pursue funds for one, as they must first identify an investigator and build a rapport with them before proceeding to secure available dates and times for the court proceedings.

Lastly, having an investigator on staff is likely related to the defender’s conducting their own investigations. Overall, 35% of all defense attorneys agreed or strongly agreed that they typically conduct their own investigations. Of defense attorneys with an investigator on staff, 18% agreed or strongly agreed that they do their own investigations, compared to 39% of defense attorneys without investigators on staff.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Shift the review and approval of requests for defense investigators and the payment for investigator services from the judiciary to public defense service providers.

A potential model to follow may be a regional or localized version of the Wayne County, Michigan, Indigent Defense Services program, which has a defense experts and investigators administrator on staff to consult with defense lawyers to identify case needs, facilitate connections with appropriate investigators, and process invoices and payments.

Recommendation 2: Take actions that promote early access to investigator services and increase investigator usage in misdemeanor and juvenile cases.

Providing methods for non-judicially controlled access to investigators, such as those seen in public defender offices and MAC programs, correlates with an increased use of investigators, and a marked uptick in usage in misdemeanor and juvenile cases. Given the significant, life-long impact both of these case types can have, it is important to take steps that raise investigator usage, most notably by removing the court as the access point to investigator services. Of similar import, removing this from court control may also increase earlier access to investigators. Some jurisdictions reported that investigators are only provided if a case is set for trial. This practice can minimize the efficacy of investigator services, as in many instances leads have grown stale, witnesses are harder to locate and have less reliable memories, and transient evidence like physical injuries, social media posts, and video recordings are no longer available.

Creating a resource pool of investigators and their areas of expertise and/or specialized skill can also minimize another barrier to access of investigator services—locating and identifying investigators who have the right skill and experience to handle a particular case type or case need, making it easier for attorneys to seek and use investigators.

Recommendation 3: Additional research is needed to determine where there may be “investigator deserts”—areas which are not served by any defense investigators.

Licensure is an insufficient method to determine who is available and willing to take court appointments for defense investigations. Not all licensed investigators perform criminal defense investigations, and not all those doing defense investigations are willing to accept court-appointed cases. As a result, more research is needed to determine whether there are parts of Texas that are lacking access to defense investigators in court-appointed matters.

Recommendation 4: Pursue practices that provide for timely, meaningful compensation to investigators.

Timely and fair compensation is critical to being able to both recruit and retain quality investigators and, more importantly, to best ensure the full breadth of relevant information is gathered and available for the defense. The U.S. criminal legal system is grounded in the principle that adversarial testing is the best way to achieve accurate and just outcomes. Without an independent defense investigation, the adversarial system would fail in its most foundational premise—the ability of both sides to marshal and present their evidence to the judge or jury deciding the case.

Because that [adversarial] testing process generally will not function properly unless defense counsel has done some investigation into the prosecution's case and into various defense strategies … ‘counsel has a duty to make reasonable investigations or to make a reasonable decision that makes particular investigations unnecessary.

Low and stagnant compensation rates and extended delays in payments undermine the premise that every defendant, regardless of their resources, be provided the “basic tools of an adequate defense.”

Promoting practices that facilitate timely payments directly to investigators when work is completed rather than when cases conclude will help recruit and retain qualified investigators. Additional efforts must be made to ensure compensation rates for investigators, like those for attorneys and other defense professionals, are adequate and are regularly reviewed and adjusted for inflation and cost of living increases. Additional considerations should be given to providing tiered compensation based on experience, expertise, and case complexity.

Recommendation 5: Provide education and training to improve the use and efficacy of defense investigators.

Training and educational resources should be made available to defense lawyers and investigators that include:

- Legal, constitutional, and ethical foundations for defense investigation.

- Effective communication and collaboration between defense counsel and investigators, including the array of skills, tools, and services investigators can provide, as well as training relating to substantive areas of practice. Special attention should be paid to the role of investigation in misdemeanor and juvenile cases.

- Training for judges on the role and import of defense investigation, as well as the legal, constitutional, and ethical underpinnings for the provision of defense investigation services. Special attention should be paid to the role of investigation in misdemeanor and juvenile cases

Recommendation 6: Improve data collection to provide a better understanding of investigator usage in Texas.

Other areas of data collection that should be addressed include the need to identify the number of cases in which investigator funds are provided. Current reporting information only requires a report of the aggregate expenditure for the prior year. This prevents any determination of whether a county is expending a lot of money on a handful of large, serious, complex cases; a minimal amount but doing so in virtually every case; or some

combination thereof.

To better understand the rate at which defense attorney requests for investigators are being made, granted, and denied, it will be crucial to collect data on all three of these points. Similar information relating to the cutting of investigator invoices and the reasons for such reductions will also be valuable in better understanding the nature and scope of that issue.

Other data recommendations include making indigent defense plan information more accessible and sortable. Although every county’s indigent defense plan is available online, the current format makes it extremely challenging to examine the information for statewide trends and practices. By creating a searchable, filterable database, communities and counties can identify practices from other jurisdictions that they may aspire to incorporate or can facilitate identification of outlier jurisdictions.

Finally, it is important to continue to collect data on investigator usage by public defender offices and MAC programs to fully understand the nature and breadth of investigator usage in the state. Collecting information on investigator requests, frequency of investigator usage by case type and task, and the impact that investigative services have on case outcomes can help improve case outcomes for all those facing criminal accusations.